How Language Might Shape Vocal Health: Exploring the Intersection of Phonoacoustics, Culture, and Recovery

Can the language you speak influence your vocal health and recovery? The Joshi Lab investigates this groundbreaking question, highlighting how different languages place unique demands on our vocal anatomy. Discover why understanding the integral link between biology and culture is vital for truly personalized and equitable healthcare.

Sanjay Balasubramanian

10/15/20244 min read

At the Joshi Lab, we're asking a question that bridges the fascinating worlds of biology, culture, and linguistics: Can the language you speak influence how vocal disorders develop—and how you recover from them? This isn't just an academic exercise; it's a vital inquiry that speaks directly to the heart of cultural competency in healthcare.

For too long, clinical voice therapy has often relied on a one-size-fits-all approach, largely shaped by protocols grounded in English phonetics. But what if this approach, while effective for some, isn't truly serving everyone? What if a patient's linguistic background is a silent, yet powerful, determinant in their vocal health journey? This is precisely what we aim to uncover. We aim to tackle how the unique phonetic and acoustic properties of different languages might contribute to the formation, severity, and even the recovery trajectory of vocal pathologies. Think about it: our vocal mechanism is a finely tuned instrument, and every language uses it in its own distinct way.

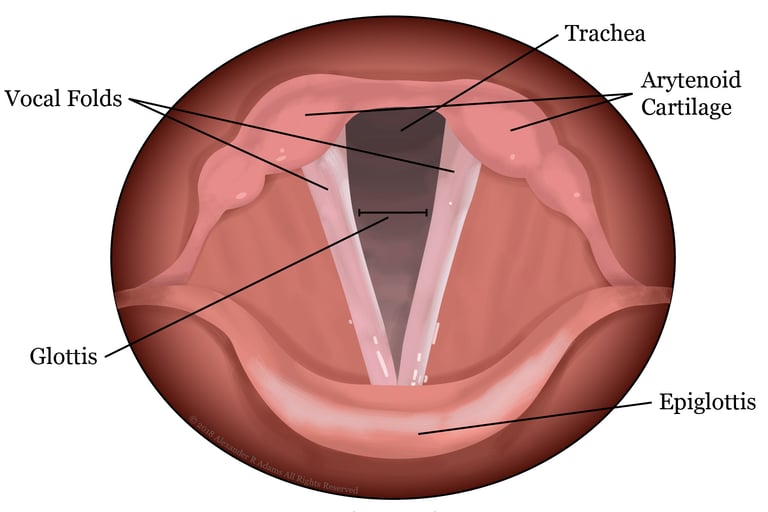

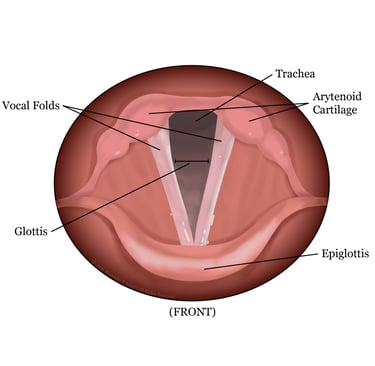

Consider tonal languages like Mandarin, where precise pitch control is paramount. This intricate requirement places unique and continuous stress on the laryngeal muscles. Or take languages like Arabic or Amharic, which frequently employ glottal stops – sounds that involve repeated, rapid impact on the vocal folds. Then there are aspirated sounds in languages such as Hindi or Korean, demanding specific airflow patterns, or the rapid articulation often found in languages like Spanish or Japanese, which could contribute to vocal fatigue under certain conditions.Each of these linguistic nuances represents a different way of "working out" the vocal apparatus. If we consider this, it becomes clear that a vocal pathology might manifest differently, respond to therapy uniquely, and even recover at a different pace depending on the patient's native tongue. At the Joshi Lab, we plan on studying patients with similar vocal diagnoses but from diverse linguistic backgrounds. By doing so, we aim to detect crucial patterns in how injuries present, how therapy outcomes vary, and what influences vocal recovery rates across different languages.

The Integral Relationship Between Biology and Culture: More Than Just Voice

Our vocal cords, larynx, and respiratory system are undeniably biological. They are made of tissues, muscles, and nerves, and they function according to biological principles. Yet, how we use these biological structures is profoundly shaped by our culture. And at the core of culture, especially in its expression, lies language.Language is not just a tool for communication; it's a living system that molds our biology over time. From the moment we begin to babble, our vocal apparatus starts adapting to the specific demands of the sounds, rhythms, and intonations of our native language. This constant, repetitive use leads to micro-adaptations in muscle strength, coordination, and even the very resilience of our vocal tissues.

For example, a speaker of a highly tonal language, like Vietnamese, trains their laryngeal muscles with a level of precision and constant engagement that is simply not required for a non-tonal language speaker. Over years, this sustained effort could lead to different patterns of muscle development, fatigue, or susceptibility to certain types of strain. Conversely, a language heavy in forceful consonants might lead to different wear-and-tear patterns on the vocal folds compared to a language rich in soft vowels. This interwoven relationship extends far beyond the vocal cords. Our daily behaviors, shaped by cultural norms and practices, can lead to subtle yet significant biological and anatomical differences across populations. Consider these fascinating examples:

Bone Density and Structure: Populations with traditionally high levels of physical activity, such as those in agrarian societies or hunter-gatherer communities, often exhibit denser bones and more robust muscle attachments compared to sedentary urban populations. The repeated stresses and loads placed on their skeletons throughout their lives literally reshape their bone architecture. Similarly, the specific types of movements and postures common in a culture (e.g., squatting versus sitting in chairs) can influence joint development and flexibility.

Diet and Metabolism: Cultural dietary patterns, passed down through generations, can lead to varying metabolic profiles and even differences in gut microbiome composition. For instance, populations with a long history of dairy farming may have a higher prevalence of lactase persistence into adulthood, a biological adaptation to milk consumption. Conversely, diets high in specific types of fats or carbohydrates, common in certain cultural cuisines, can contribute to different predispositions for metabolic conditions like type 2 diabetes or cardiovascular disease within those groups.

Musculoskeletal Adaptations: Repetitive tasks common to certain crafts or professions, often culturally transmitted, can lead to unique musculoskeletal adaptations. For example, traditional weaving or pottery can lead to specific hand and wrist muscle development. Even how children are carried (e.g., in slings on the back versus front-facing carriers) can influence infant hip and spine development.

Vision: While largely genetic, environmental and cultural factors can influence the prevalence of certain vision conditions. For example, some studies have explored whether prolonged close-up work, increasingly common in technologically-driven societies, contributes to higher rates of myopia (nearsightedness) compared to societies where far-sighted activities dominate.

This interwoven relationship means that our biological predispositions and responses are not isolated from our cultural practices. Instead, they are in a dynamic feedback loop. Our biology provides the foundational capacity, but our culture dictates how that capacity is actualized, stretched, and, at times, stressed.

Why does this matter for cultural competency in health?

This research is fundamentally about recognizing and respecting the diverse experiences of patients. It highlights that effective healthcare isn't just about treating a diagnosis; it's about understanding the whole person, including the profound influence of their cultural and linguistic context.

Imagine a patient whose vocal cords are strained from years of speaking a tonal language, receiving therapy designed for someone whose language uses different vocal demands. The treatment might be less effective, or even miss crucial elements contributing to their condition. By exploring the language-vocal health connection, we are advocating for:

Personalized Care: Moving beyond generalized protocols to develop more tailored, linguistically informed therapeutic interventions.

Equitable Outcomes: Ensuring that all patients, regardless of their native language, have access to the most effective and appropriate care for their vocal health needs.

Deeper Understanding: Fostering a more nuanced understanding among clinicians of how linguistic diversity impacts the presentation and management of vocal disorders.

Challenging Assumptions: Encouraging healthcare providers to question existing norms and consider the broader cultural and linguistic factors that shape patient health.

Our work at the Joshi Lab is a call to action for a more culturally competent and linguistically informed approach to vocal health. By understanding how the very words we speak can shape our vocal well-being, we can pave the way for more effective, equitable, and truly patient-centered care for everyone. Stay tuned as we delve deeper into this fascinating intersection of language, culture, and health!